Identity Soup

An exploration of the limitations we put on non-white artists

As I am a good deal late to the party, I don’t want to wade too deeply into the recent debate stirred up by Dean Kissick’s December 2024 cover story of Harper’s Magazine, titled “the Painted Protest,” which considers the flattening of contemporary art by the insistence that art be a political tool focused on representation and identity.

There’s been plenty of debate already about whether the article is reductionist, obvious, or a breath of fresh air. (I might insist it’s a bit of each.)

As a person running an organization dedicated to women, there are many facets of the article I could respond to, but I’ll pick one for now, from close to the end of the essay, in which Kissick laments the way art has melted into a soup of marginalization: “Everywhere, differences have flattened and all forms of oppression have blended into one universal grief,” he writes.

While Kissick blames the artists too much for this flattening, I think much of the blame should fall on the curators, writers, and other interpreters of the work who have tacitly identified (in wall labels, headlines, and press releases) non-white artists as working towards the same goal: to subvert the hegemony of the white, male Western canon.

It sets up a conflict that one side doesn’t even know it’s waging: non-white artists fighting against canon, while white ones (in large part) can placidly go on reinforcing it, escaping the need to acknowledge their identity at all. (Something the critic Ajay Kurian points out in his rebuttal to Kissick’s piece.)

If that is the case, we’re forced to judge all non-white artists on that rubric: not the mood the work evokes or the quality of brushstrokes or even “are they technically skilled?”, but rather “how well have they defied the canon?

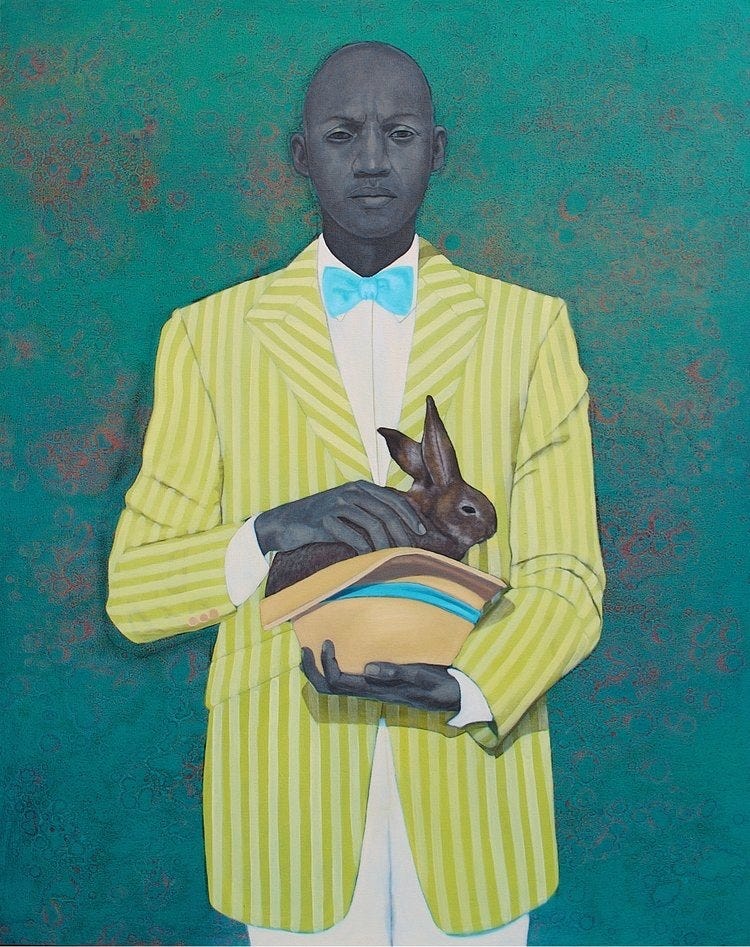

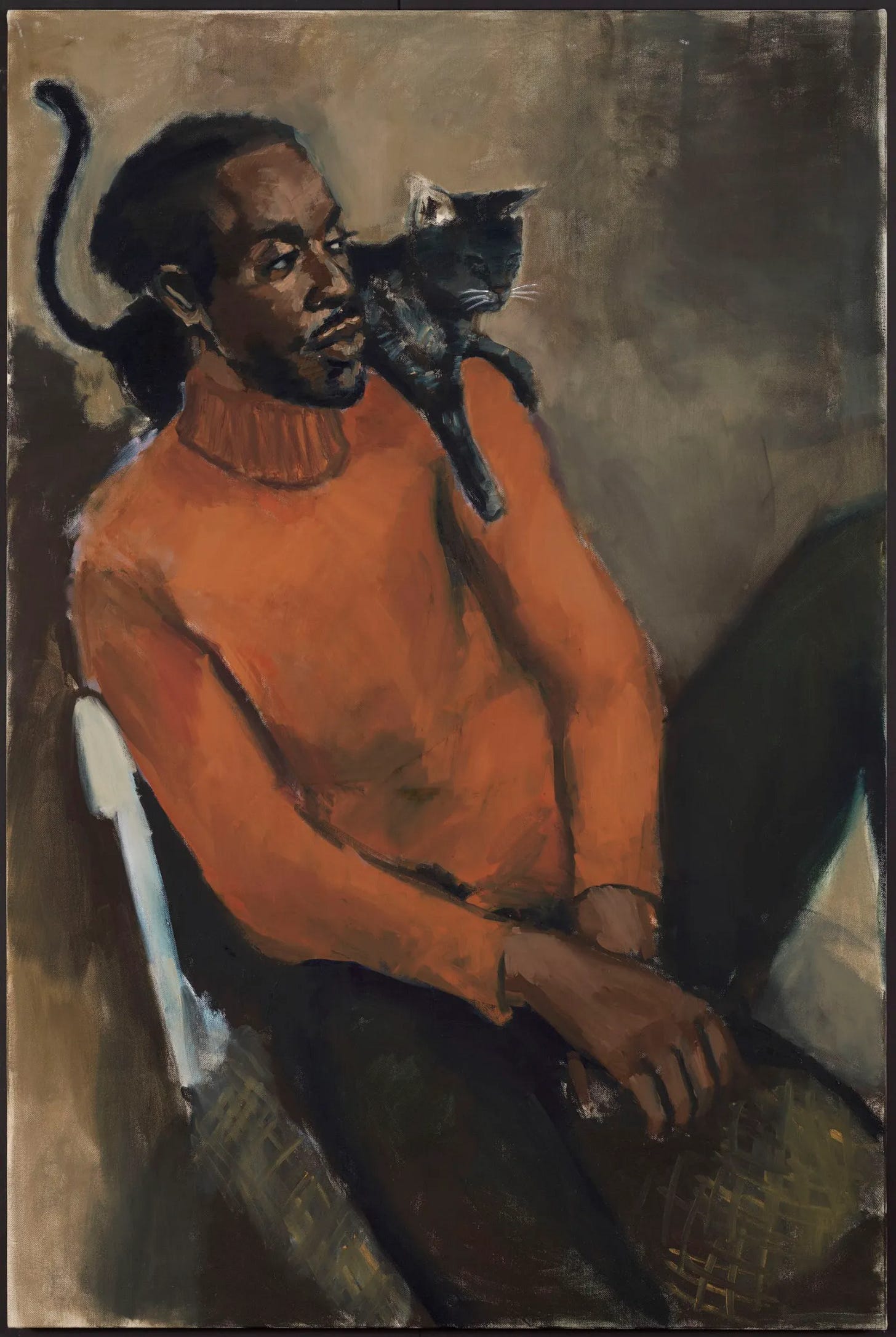

There is an enormous difference between the work of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Amy Sherald. But if this is our only rubric to judge artists whose work even touches on identity, two Black women painting portraits of Black people are ostensibly the same.

From this point of view, Sherald might even be the “better” artist: her work is more political (she did paint Michelle Obama’s official portrait), her subjects’ direct gaze more confrontational.

However, I think the opposite. As artworks, I find Yiadom-Boakye’s vague, brushy, sometimes sad figures brilliant, but Amy Sherald’s bright full frontal portraits unremarkable and wooden. (Ironically, Yiadom-Boakye is far more skilled in evoking human spirit, despite the fact that she paints imagined people.) I’m afraid identity-based interpretations of the work don’t give us the words to be able to express these (very obvious when you look at them) differences. What a disservice that is to these artists.

And what does the rubric say about the merits of a non-white abstract painter, or anyone whose work falls outside figuration? What of Howardena Pindell’s abstractions, strewn with hole punch confetti? In a podcast discussing the article, critic Ben Davis mentions a friend who felt the market was forcing him to make art based on his non-white identity, when he had little interest in doing so.

So where do we end up? Ironically, identity politics in art limits what the artist can say— and what we can say about art. If there is a “blended universal grief,” it’s a soup without salt, seasoning, or aromatics.

You make a sharp point about how identity-based framing can flatten artistic nuance. As a woman artist—though not an artist of color—who explores body, gender, motherhood, and identity, I see how market forces and curatorial narratives often box artists into a narrow rubric of “defying the canon.” It’s a disservice when artists like Yiadom-Boakye and Sherald, with vastly different approaches, get lumped together simply because they depict Black subjects.

The issue isn’t identity in art—it’s how it’s framed. Artists should be free to engage (or not) with identity on their own terms, without being reduced to a single expectation. We need space for both resistance and ambiguity, allowing for complexity rather than forcing a universal narrative. How do we push for that shift?

I agree with you on this article. While it is a larger conversation, I would say I don’t escape my identity as a white female artist, which implies a sort of laziness and arrogance. I don’t think about it until I’ve made the work and then attempt to figure out what I’m trying to express. Some of us (white/nonwhite) are more political in our lives, and make work about another side of our psyche. I am aware of being female when I market the work and sometimes it involves the work, sometimes not. It probably comes into play more when I am looking at the work of others and exploring its meaning.

It IS a soup, and far more layered than what curators think it should be. I’m sure there are some artists who are more global, some more personal, and some who try to make work they think is relevant to current themes or are driven by what they think the world will respond to.

While this often is written about painters, it is about all of us. There is no universal narrative as Sally says in her comments here. Kind of theory vs actual practice.