CW: Part of this post explores the theme of violence against women.

In honor of Presidents’ Day (mattress sales), I thought I would explore the surprisingly rich terrain of women using mattresses in their work.

Blankets, of course, are frequent in art by women— from the story quilts of Faith Ringgold to the blanket towers of Marie Watt— and so are bed scenes — from Marie Cassatt’s mother and child in bed to reinterpretations of the art historical cannon’s lounging ladies (think Mickalene Thomas’s Odalisques or endless versions of Manet’s Olympia).

But the mattress, most often presented physically with no occupant, is a charged object unto itself.

Of course, men use mattresses in their work, too. I always find terrain like this interesting— I don’t think “women’s art” is a thing, necessarily, but I do think that women have experiences that men largely do not, whether socially or biologically imposed. Women artists find their own language to communicate these experiences. Compare Rauschenberg’s Bed, with Tracey Emin’s My Bed and you will immediately spot the difference— in the hands of women artists, mattresses have an emotional valence that I don’t see anywhere else.

So let’s dive in:

Mattresses are often used as vehicles to communicate sexual desire or sexual anxiety — as in Sarah Lucas’s bare mattresses that are both funny and sad, evoking sexual desire while implying unfulfillment.

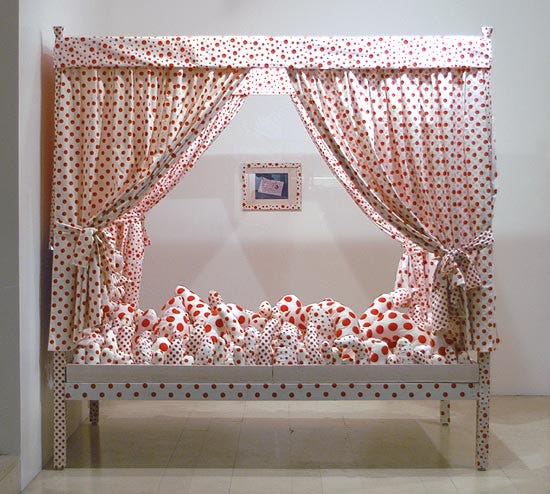

Yayoi Kusama’s Bed-Dots Obsession, on which phallic protrusions proliferate, calls to mind the artist’s professed anxiety around sex, born of a traumatic childhood experience.

At other times, the mattress is much more explicitly laden with trauma, a symbol for when a site of comfort and refuge becomes the site of physical violence.

In Carry That Weight, Emma Sulkowicz carried her campus issued dorm mattress with her to classes at Columbia, vowing to bring the mattress with her until the man who had sexually assaulted her was expelled. Ana Mendiata explored sexual assault and violence against women in a body of work I still find shocking. The series featured the staged aftermath of a rape— including Bloody Mattresses, where the artist piled dirty mattresses in an abandoned farmhouse. In her series, She Was Last Seen, Katelyn Kopenhaver takes a similar tack, leaving mattresses covered in the eponymous message scrawled with paint in galleries or public settings.

But it’s not all trauma—

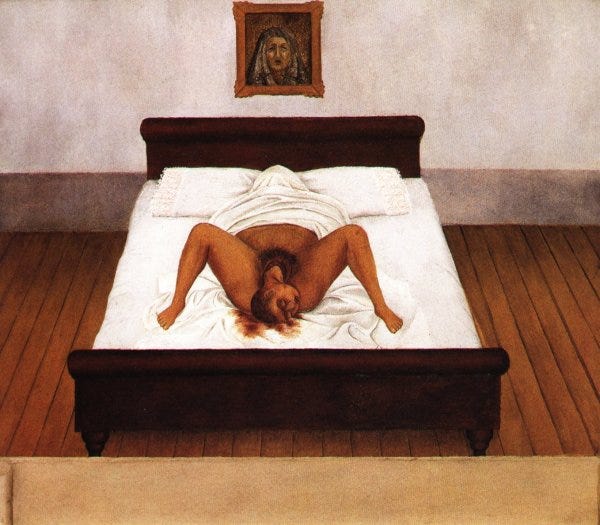

For Frida Kahlo, who spent significant time on bedrest after a crippling accident, the mattress was a place of selfhood. While My Birth does depict childbirth, the painting’s high vantage point, which pushes the white square of the mattress toward the picture plane, makes the mattress look like a canvas. The adult head of Kahlo emerging from an anonymous body with her face covered, suggests she was born an artist, making her life a work of art.

Lucia Hierro, whose work I’ve mentioned here before, uses mattresses to evoke the visuals of street life, where mattresses standing propped on the sidewalk waiting for trash pick up, are a common site.

Others find rich terrain in mattress foam as a material, as Barb Smith does, soaking it in a substance that ensures it keeps its shape. Setting them upright, like standing figures, the relationship between the body and mattress is made visual.

So, happy Presidents’ Day, go get yourself a good deal on a mattress, and let me know which artists I’ve missed below!

Very creative read - loved it !

I was finishing a Masters at Columbia when Emma was walking around with her mattress. What I remember so poignantly were the wonderful students who walked around with her or even kept up the vigil of carrying the mattress themselves when she could not.